Our visit to a Chinese hospital was a bit of a culture shock, even after living here for a year and a half. It was not the way I’d have chosen to spend an afternoon, though I’ll admit, I’ve been curious about China’s healthcare system ever since I got here.

Needless to say, Chinese hospitals are quite a bit different from American hospitals. Despite the differences, it really wasn’t so bad. Most importantly, nobody is seriously hurt or sick. All parties concerned are lying in bed recovering.

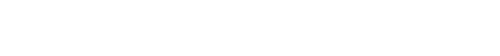

Here comes the ambulance

I was on my way out the door when I heard a thump and a yell. I ran in the bedroom and found Rachle laying on the floor, clutching her knee. She couldn’t move or walk without tremendous pain. We called our boss to say we wouldn’t be in to work, and to ask if someone could help us go to the hospital.

One of the frustrating things about living in a foreign country is that you need help doing any sort of adulting. You can’t help feel a little bit like a child, needing someone to hold your hand for any and all official business. I’m definitely thankful we know people who are willing to help us with these sorts of things.

Our boss sent the intern, Amy, to help us out. We had thought we could get Rachle down the elevator between the three of us, but it was too much. We had to call an ambulance.

The paramedics came in about fifteen minutes or so. They hauled in a big yellow stretcher that barely fit in the hallway. Amy translated what had happened to the paramedics, and they helped Rachle onto the stretcher. They were also, apparently, quite taken with how we’d decorated our apartment.

Thankfully, none of the neighbors were out staring at his as we left. The Bao An (apartment security person) looked at us concernedly from her office, but that was it. They wheeled Rachle across the parking lot to an ambulance that looked more like a big minivan than anything else. We got in the back, and I got my first ambulance ride.

When we got to the hospital, nobody would move out of the way to let the ambulance into the emergency room area. I wanted to get out and yell at them to move. “Chinese people don’t take ambulances seriously,” Amy told us. “They probably think someone just sprained their finger.”

Registration and Chinese hospital cards

The paramedics dropped us off in the emergency room reception area at Zhongshan hospital, a big public hospital here in Shanghai. We stand awkwardly in front of the door while Amy ran off to rent a wheelchair for us. Wheelchairs and stretchers aren’t supplied by the hospital, apparently.

The first step was to register with the hospital. We had to go to a window and buy a little card, which looks like a credit card. Each hospital has its own card. Then we went back to the reception area and got a slip of paper, which we took to some machines back by where we got the card to pay for the consultation with the doctor.

Once that was paid for, we waited outside the doctor’s office. I expected someone to tell us to go in, or give us a number or some indication it was our turn. Instead we just walked in when the previous patient left. A burly construction worker followed us in, and waited in the doctor’s office while Amy translated what had happened. The doctor looked at Rachle’s knee, and then gave us another slip of paper. The construction worker held the door open for us as we went out.

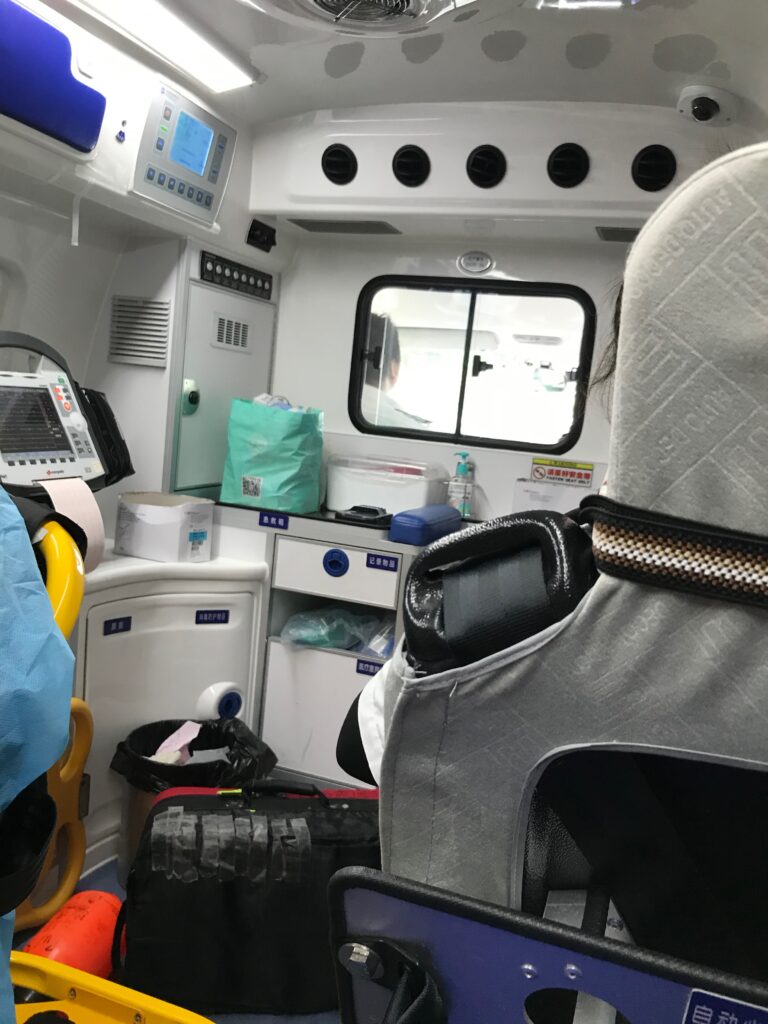

We took the elevator up to get some X-rays. This time, we had to take a number. We waited for a few minutes, then wheeled between two big metal sliding doors into the X-ray room. The biggest wait of the day came when we sat for about an hour waiting for the X-rays. We then took the X-ray results and rode the elevator back down to see the doctor.

He gave his diagnosis, a displaced kneecap, although he used the medical term which I don’t remember. He was very helpful, and actually quite kind. “Sorry for my horrible English” he said, with perfect pronunciation, as we were leaving. He printed another piece of paper, I went and paid using the card and the little machines, and then we wheeled off to get a knee brace fitted.

Like a DMV for sick people

The whole process was pretty efficient, despite all the back and forth, and feeling a bit like we were in a DMV for sick people. We probably spent three or four hours total, from the ambulance ride through to wheeling Rachle back home. Overall, it was pretty painless. For me, anyways.

That’s not to say it was pleasant. I feel like I looked death in the face.

In the initial waiting area, there were old people laying on stretchers in the middle of the hallway with tubes and wires dangling from their bodies. Two women wheeled a man with a distended belly into the bathroom next to us, where he started noisily vomiting.

There was a group of three men in construction uniforms that came in with us, including the guy who watched the diagnosis. They didn’t have a wheelchair or stretcher or anything. The two healthy men took turns carrying their friend piggy-back back and forth to the different rooms and windows. I glanced over just in time to see the guy lifting his sleeve to show long, bloody gashes in his arm.

In a weird way, it was almost inspiring, though. It takes a true friend to carry you around a hospital.

While we waited for the X-ray, some uniformed hospital officials wheeled an old woman with a face wrinkled like crumpled paper past us. She stared blankly at the ceiling. I’m pretty sure I heard death rattle as she went by. Amy shuddered and turned to me right after she left. “I hate Chinese hospitals,” she said.

Life is only temporary. We’re very far removed from that in America.

Healthcare in China

I was actually surprised to learn that healthcare in Communist China isn’t exactly free.

After the 1949 revolution, healthcare was nationalized. Thousands of “barefoot doctors” were sent throughout the country to provide medical care to people who couldn’t afford it otherwise. Community health collectives were started, and in general, healthcare was taken care of by the government. What you’d expect from communism, really.

In the 1980s, though, as part of the general opening up of the economy, there was a push to privatize healthcare. This led to millions losing health coverage, though health overall improved due to better diets and so on. The health care system crisis peaked during SARS epidemic in 2003. Since then, there’s been a move to reform healthcare in China. The government now provides medical insurance to all citizens, though it doesn’t cover everything.

It seems like healthcare as a whole is now a bit of a patchwork mix between socialized medicine and Obamacare. Insurance is mandated, and you can choose between the government insurance and private insurance if you can afford it. Again, it doesn’t cover everything. Also, you have to pay for everything up front, then submit a claim and get reimbursed.

So, how much does a Chinese hospital visit cost?

The grand total (not including crutches), from the ambulance ride, to the hospital registration, to the x-ray came to 390 RMB.

In comparison, we went out to eat with a friend the night before and paid 310 RMB.

If you count the crutches, the grand total came to 520 RMB. That’s about $75 bucks in U.S. money.

For reference, a brand-new copy of Marvel’s Avengers: Deluxe Edition for PS4 costs $79.99 on Amazon. Not including shipping. A hospital visit, complete with ambulance ride, X-ray, brace and crutches cost $4.99 less than a video game. Not including shipping.

And, we’ll probably get most of it reimbursed.

I’m guessing a lot of healthcare is subsidized to keep it so cheap. Also, doctors here apparently aren’t as rich as they are in the states. They aren’t poor, and they still have to go through pretty rigorous schooling and training, but they aren’t driving around in BMWs and playing golf in fancy resorts like U.S. doctors. It’s also important to remember that the average wage is only 10,000 RMB a month in Shanghai. So, while 520 RMB may seem like nothing to us, it’s still quite expensive for local people.

Still, I think Chinese people go to the hospital much more often. Every time I get a cold, my Chinese coworkers ask: “Did you go to the hospital?” My response: “why would I go to the hospital for a cold? I’m not made of money.” As an American, I still feel like going to the hospital for anything less than a missing limb feels like a bit of a frivolous luxury.

In the end, though, if you’re going to get sick or injured, you could do a lot worse than a Chinese hospital. Just make sure you bring a friend or an intern who can speak the language.