So, you’re thinking of learning Chinese, are you? Great idea. Not only is it a fascinating language, but it’s also spoken by over a billion people. Learning Chinese will give you insight into the enthralling, large, sometimes beguiling nation of China. Get ready to open the doors to one of the world’s great, historic cultures.

As you maybe already know, there are numerous varieties of Chinese. The most famous are Mandarin and Cantonese. You also might know that there are two varieties of Chinese characters, the traditional and the simplified.

This article will focus on learning Mandarin Chinese with simplified characters since that’s what I did. However, I think the basic principles should apply if you want to learn traditional characters and study Cantonese or Shanghainese or whatever.

It’s a long and difficult journey, but learning Chinese is without a doubt a rewarding adventure.

Learning Chinese is Difficult

First thing’s first. There’s a whole cottage industry out there of people trying to sell you on the idea that learning Chinese is easy. Even one adorably named “Chineasy” complete with cutesy Pinterest-ready drawings of the characters. I wish learning Mandarin Chinese was a brightly colored skip through the park, but it’s not.

Chinese is not easy. It is a really, really difficult language, especially for English speakers. Anyone who says otherwise is probably trying to sell you something.

Maybe I’m being too cynical. There are probably some well-meaning individuals who are just trying to motivate people to learn. The problem is that if you go around telling people Chinese is easy, what happens when those people find themselves staring at a newspaper full of incomprehensible characters or facing down a cab driver who is speaking twice as fast as he’s driving? Those people often give up.

That’s why I think it’s important to just be honest about it. Once again, learning Chinese is really hard.

However, the older I get, the more I realize that the difficult things in life are the most worthwhile. If you put in the effort to learn Mandarin, that moment when you figure out what the newspaper article is about, or have your first conversation with a cab driver will be all the more sweet. Plus, your hard work and effort will let you feel morally superior to those lazy bastards learning Spanish.

How Do You Know How Good Your Chinese Is?

The Chinese are lovely people, but they can be overly complimentary to foreigners. You might barely be able to produce a mangled “nihao” and your Chinese friend will respond with “oh wow, your Chinese is sooooo good!” So, how do you know what your Chinese level actually is?

Thankfully, there are the 汉语水平考试 a.k.a. Han Yu Shui Ping Kao Shi, a.k.a. HSK tests to guide you. The current version has levels ranging from one to six. However, in April of 2021, the Chinese Ministry of Education announced they would be updating and revising the HSK. It’s now nine levels.

This is probably a good thing, because, to be honest, the current levels seem a little arbitrary and are in need of some updating. That jump from four to five is a doozy.

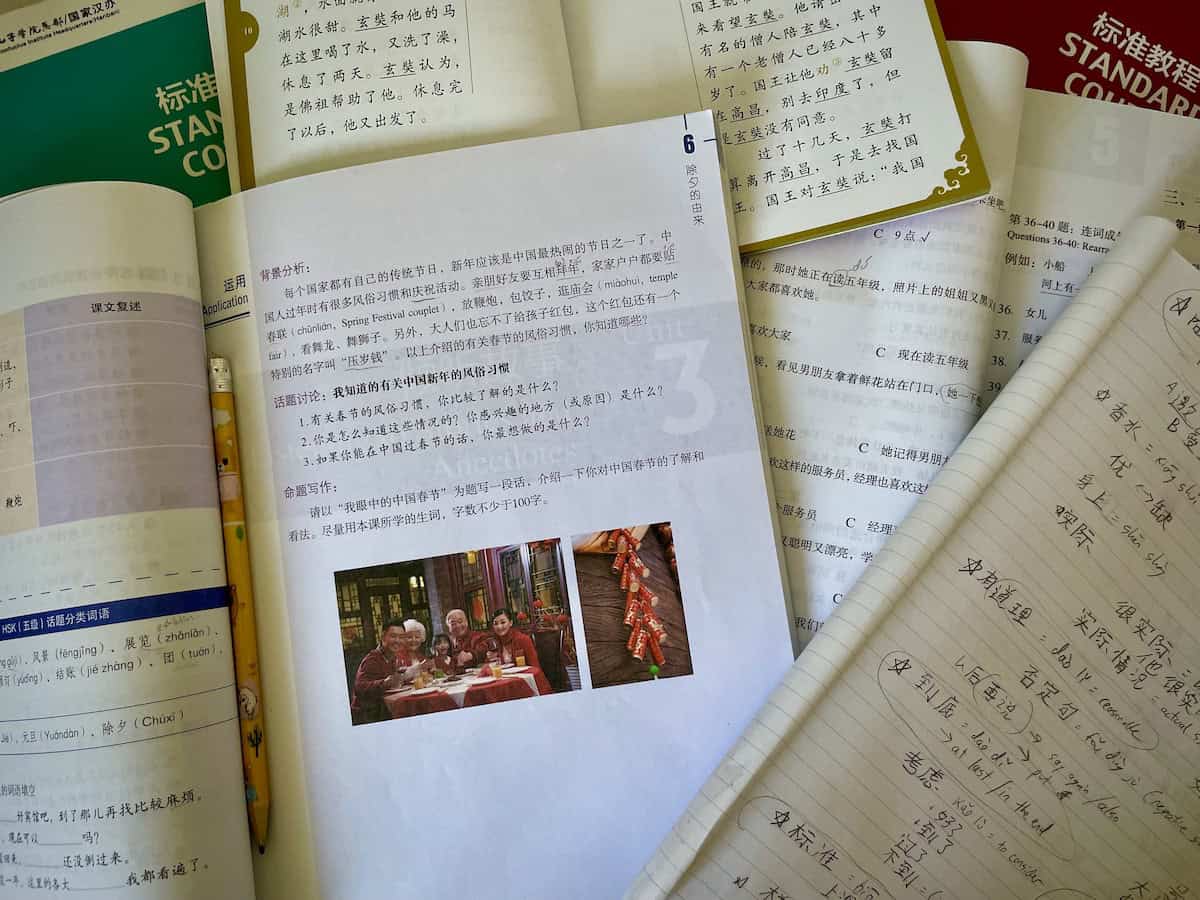

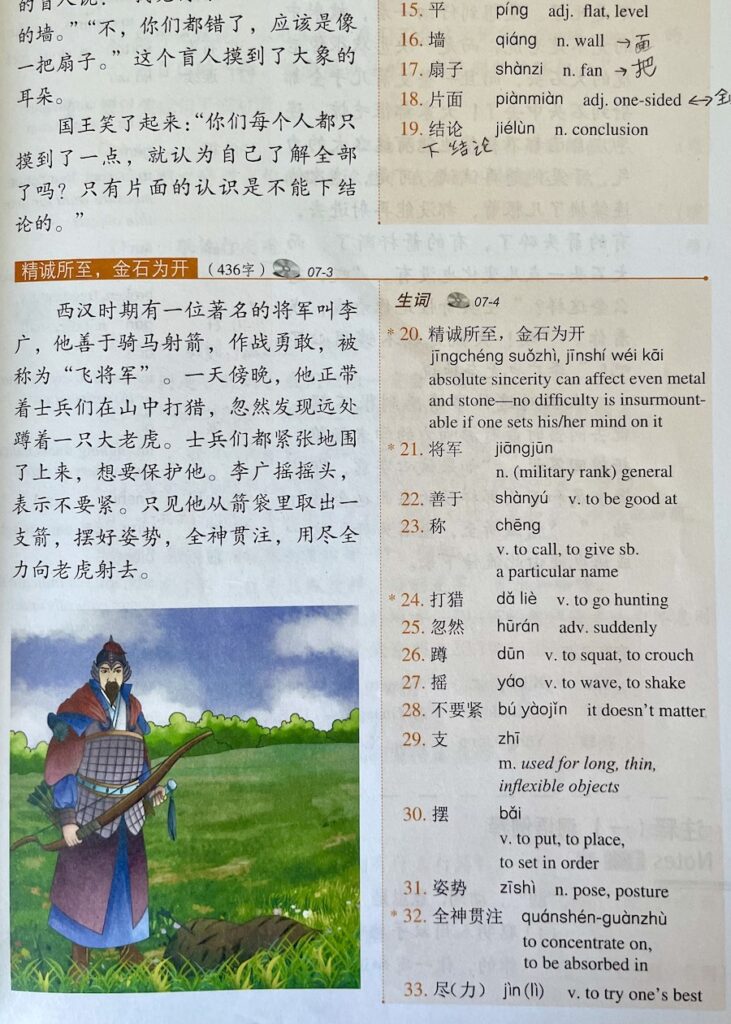

Despite that, I would still recommend the official HSK textbooks. Even if you have no intention of taking the test. They introduce vocabulary in a nice, logical order, and do a good job of reviewing words you’ve already learned in later chapters. The early books are mostly dialogues, while later books have articles adapted from actual Chinese magazines and newspapers.

Though the official HSK textbooks are far from perfect, they’re the best of all the Mandarin Chinese textbooks I’ve tried (and I’ve tried a few). As a bonus, they don’t try to introduce you to any of the cornball characters, like the hapless American foreign exchange student or dopey businessman, who tend to populate most other language learning textbooks.

Should You Self Study or Take Chinese Classes?

If you type in “how to learn Chinese” on YouTube you’ll find about a thousand videos from self-proclaimed polyglots claiming they’ve taught themselves fluent Chinese in three months. They’ll also probably have some videos titled “White Guy Shocks Chinese Restaurant Workers by Ordering in Fluent Chinese!”

If your entire goal for learning a language is to prove your racial superiority by one-upping the natives, please do the world a favor and shut up. You’re a dick.

But, I digress. The question was about self-studying versus taking classes. They both have their advantages and disadvantages. Spoiler alert: I think you need to do a little bit of both.

Self-Studying Chinese

Self-studying is important. Even if you take classes, you’ll need to put in a lot of work on your own anyway to finish your homework and review the lessons. These things are essential in order to make the class worthwhile. If you do everything by yourself, you can study whenever you want, and make use of the numerous free online resources out there. There’s also a sense of satisfaction, knowing you accomplished something all on your own.

The biggest downside of studying Chinese by yourself is that you won’t have anyone to correct your mistakes. You run the risk of building some bad habits that might be hard to break later on.

There are also grammar points or vocabulary words you might miss by just studying on your own. You can certainly catch up later, but you may be a little embarrassed when you tell people you’ve studied Chinese for years but you don’t know how to ask for more water in a restaurant.

Finally, I think the speed you progress when self-studying can often be much slower than in class. I spent a little over two years studying Chinese on my own. I was able to reach about HSK 3 during this time. When I started taking classes, I jumped from HSK 3 to 4 in a matter of months.

Learning Chinese in Class

I think most language classes are garbage, especially the ones we get in high school or college. There is absolutely nothing helpful about sitting in a lecture hall with twenty other people listening to a teacher drone on about grammar. You might learn how to take tests and do worksheets, but you won’t ever really learn the language.

So, when I talk about taking Chinese classes, I’m talking about taking the right Chinese classes. What does the right Chinese class look like?

First, your teacher should mostly speak Chinese. Ideally, the class should be 90% in Chinese. English should only be used sparingly if there’s absolutely no other way to explain something. A native-speaking teacher is best, since they’ll have a native accent and can also explain some cultural insights and linguistic nuances.

Second, the class should be small. One-on-one lessons are great, but they’re more expensive. Three or four people is good, six students maximum. You want as much time as possible to practice speaking and interacting with the teacher. The best is to sign up for a group class and hope your classmates never show up.

A good native Chinese teacher will help you understand the context of words and phrases that you’ll never pick up from a book. They’ll correct your mistakes, and classes can be a great motivator. There’s nothing more embarrassing than showing up to class and having to admit that you didn’t study the week before.

There are downsides, even with the right class. Chinese classes can be damned expensive. They are also more rigid. You have less wiggle room to pursue aspects of the language you find personally interesting. You’ll also have to find room in your busy schedule to commit to classes.

Classes and Self-Study, the Magic Combination

In the end, I think classes are definitely worth it. However, as I mentioned before, they aren’t enough on their own. You can’t learn a language in one or two hours a week. The key is to combine your self-studying with your formal lessons. Maybe it’s best to think of formal classes as a guide and a motivator for your self-study.

One really cool thing would be to do an immersion program, where you not only take classes but also stay with a Chinese family. I did this in Nicaragua while studying Spanish, and I saw my level skyrocket in just two weeks. Unfortunately, thanks to the dumb pandemic, it looks like I’m not going to get the opportunity to do this in China. Maybe someday.

I have had good luck with a school called Mandarin Inn here in Shanghai. It isn’t a full immersion program, but their classes generally check all the boxes. Just don’t be shy about asking to switch teachers if yours doesn’t quite click. If you’re coming to Shanghai and want to take Chinese classes, I’d recommend them.

If you can’t make it to China and want to take classes, you can also always look on iTalki. I’ve mostly taken conversation classes, but you can also find more formal lessons if that’s what you want. Online classes are a poor substitute for in-person classes, but iTalki can still be a great resource if it’s the only option you’ve got.

What About Apps for Studying Mandarin?

Everybody loves their apps these days, and it makes sense. Apps can make language study convenient and easy. There’s also something to be said for the way certain language apps try to gamify language learning and make it more fun than a stuffy old workbook.

However, I’d be careful when using apps to learn Chinese. A lot of people love Duolingo, for example. But, every single person I’ve met who uses Duolingo to study Chinese speaks the language absolutely terribly.

I think the problem with Duolingo, as well as Rosetta Stone and many other language apps, is that they are built for learning European languages. Rather than adjust the app to fit Chinese, they instead try to force Chinese into the framework of their app. Duolingo or Rosetta Stone might work for French or Spanish, but it’s just not going to cut it for Chinese.

Aside from Anki and Skritter, which I talk about below, the only other Chinese learning app I’ve had success with was Hello Chinese. The format is very similar to Duolingo, but the app is made especially for learning Chinese. It also has some very good listening practice to get you used to how Chinese people actually speak. It’s not a substitute for classes or other self-study methods, but I think it can be a useful tool for learning Mandarin Chinese.

The Convoluted Step by Step Guide to Learning Chinese

I’ve listed all the steps I’ve used to learn Chinese below. Unfortunately, much like life, the reality of learning Mandarin Chinese tends to be a lot messier than any clearly defined step-by-step instructions. To be completely honest with you, I basically do all of these steps at the same time. I’m learning vocabulary while I’m fine-tuning my pronunciation and trying to immerse myself in the language. It’s all equally important and none of it can really be neglected. So, with that disclaimer out of the way, here’s how to learn Chinese.

Step One: Pronunciation, You’re a Chinese Baby

The very first baby step you need to do is teach your mouth to make actual Mandarin sounds rather than garbled nonsense. Accept the fact that you’re probably going to have an accent no matter what. That accent will make you sound real sexy when you come to visit China.

Chinese is a tonal language. This means that the meaning of a word changes depending on the pitch or tone you use. Standard Mandarin Chinese has five tones. The classic example is mā, má, mǎ, mà, ma (妈,麻,马,骂,吗).

The first mā means ‘mother’, the second má means ‘hemp’, the third mǎ is ‘horse’, the fourth mà means ‘to scold’ and the last, neutral ma gets added to the end of the word to make a question. Confused? The tones are part of the reason Chinese is so difficult for speakers of European languages.

The good news is that the tones themselves aren’t that difficult to learn. You don’t have to worry about your actual pitch, just how your pitch changes relative to your normal speaking voice. This YouTube video from YoYo Chinese gives a pretty good introduction to all the tones.

The difficulty comes in remembering which tone goes with which word. That’s something I still struggle with after studying Chinese for years. Generally speaking, Chinese people will be able to tell what you’re trying to say from context if you mix up your mā and your mǎ. (Or maybe you really were raised by a horse?)

Accept that you won’t be perfect, but don’t neglect the tones. They’re an essential part of the language.

Step Two: Pronunciation, Welcome to Chinese Kindergarten

The next thing you need to do after getting your head around the tones is to learn the rest of Mandarin pronunciation. Thankfully, the pronunciation system is much more standardized and logical than this crazy mess we call English.

There’s a writing system for Chinese using the Latin alphabet called Pinyin, and it’s super helpful for learning Mandarin. There were plans back in the day to do away with the characters altogether and just convert the language to Pinyin. It didn’t work out, but they do still teach it to Chinese kindergarteners and you’ll see it on some old propaganda posters.

The vast majority of the letters in Pinyin are basically pronounced how they are in English. The ones you really need to worry about are “q” “c” “x” and sometimes “u”. The “q” in Pinyin comes out sort of like a weird “tch”, the “c” is almost like a “ts” and the “x” is somewhere between English’s “s” and “sh”. “U” can sometimes be like an English u, or it can be like some weird French “ü” or when combined with an “n” it can sometimes sound like the word “when.” Don’t worry, you’ll pick it up.

Now, technically, if you want to have a perfect accent and trick people into thinking you’re a native speaker on the telephone, you can’t just pronounce the rest of the letters exactly like English. There are a lot of different nuances in tongue and teeth placement.

However, if you pronounce your Chinese “r” and your “ch” like a good old all-American “r” or “ch”, people will know what you’re saying. Remember, you’re going to have an accent no matter what. The goal is to be understood.

Here are some resources for learning Pinyin (it’s also covered in the HSK textbooks):

https://resources.allsetlearning.com/chinese/pronunciation/

https://www.chineseclass101.com/chinese-pronunciation/

Step Three: Vocabulary, Learnin’ Words

Now comes the fun part. Learning vocabulary. I know, it doesn’t sound like fun, but it actually really can be. Your main tool for learning Chinese vocabulary will be a wonderful, mostly free, program called Anki. Anki is a spaced repetition program, that basically shoves words into your brain and then makes you review them right before you’re about to forget them. It’s great for memorizing anything.

The only downside is that it’s also a little bit complicated to set up. Here are a few resources on how to do that:

https://discoverdiscomfort.com/how-to-use-anki-flashcards-language/#get_started_with_anki

https://www.fluentu.com/blog/anki-language-learning/

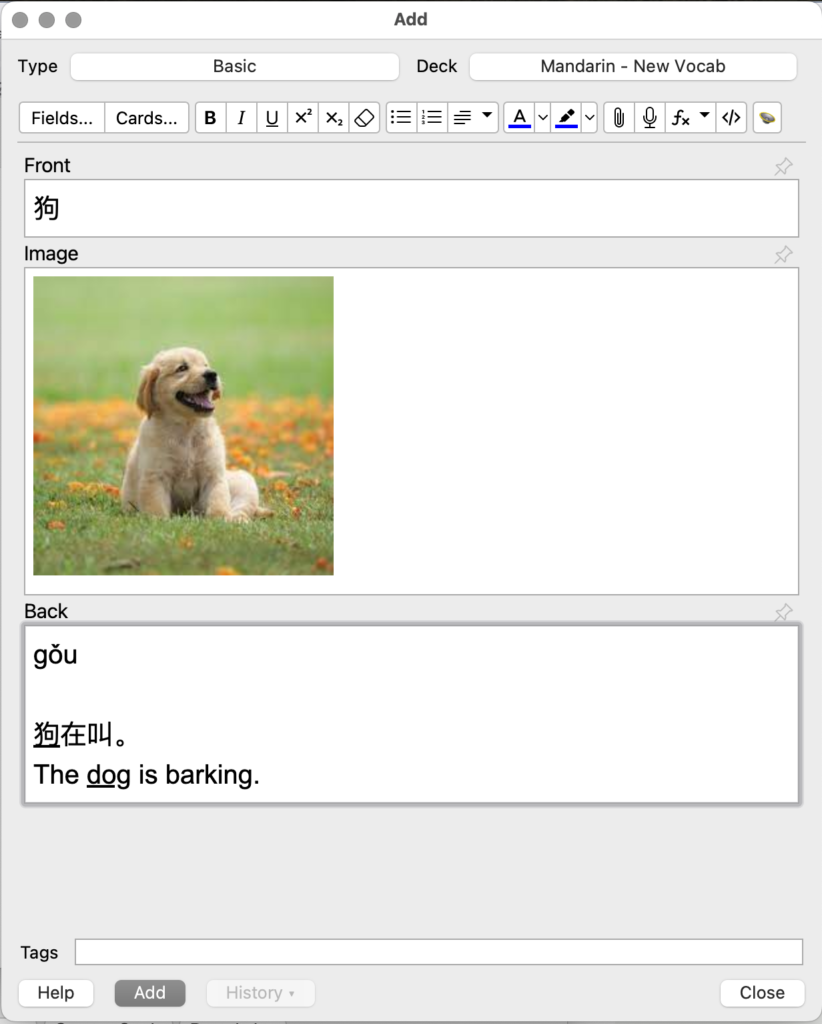

There are a million premade Anki decks available online for free. Don’t use them. It’s important to make your flashcards yourself. This extra step can be time-consuming, but it’ll really help you to get those words into your long-term memory.

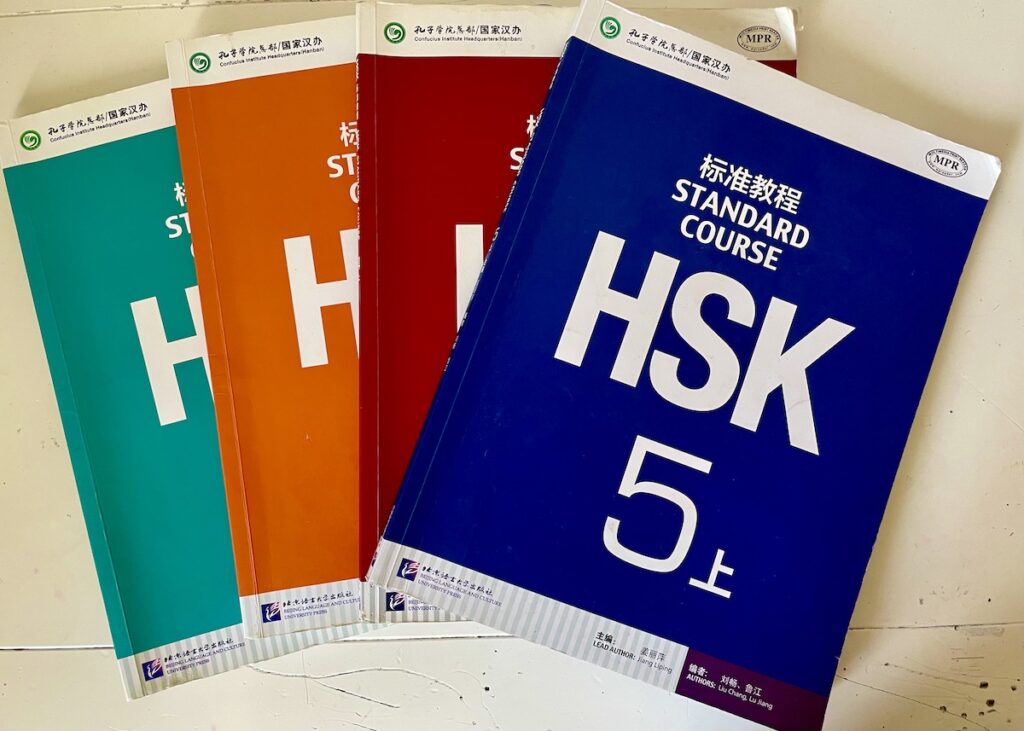

As much as possible, try not to put the English translation of the word in your Anki cards. Use a picture whenever you can. This is easy for nouns like table and cat, but a little more difficult for more abstract words, like imagination. You can get creative with it, maybe use a scene from a movie or TV show that reminds you of the word. If you absolutely can’t find a suitable picture, at the very least use google images to find a cool stylized picture of the word. This will be way easier to memorize than just some boring typing.

Also, make sure you have an example sentence. This will help you remember how to see the word in context. When you’re starting out, you can have an English translation under the sentence, but eventually, you want to get to the point where your example sentences are all in Chinese, too. I use these sites for most of my example sentences, but if you’re taking words from your textbook, you can also copy the sentences from the book.

https://www.yellowbridge.com/chinese/dictionary.php

https://www.purpleculture.net/sample-sentences/

Your basic Mandarin Anki flashcard should generally have the Chinese character on one side, a picture, and the pinyin plus an example sentence on the back. If you really want to get fancy, you can add audio and other tools to help you with pronunciation. The sky’s the limit with Anki.

When Should You Start Learning Characters?

You should start learning Chinese characters as soon as you can. I know there are people who say you don’t need to bother with the characters. After all, if we can just read Chinese using Pinyin, why not just do that?

Well, not only are the characters a beautiful part of the language and culture, but they also really help you to learn the words. Each Chinese character is like its own compact, mnemonic device.

Take our good friend, 妈, for example. On the left-hand side, you’ve got 女, the character for “woman”. This tells you your 妈 is a woman. On the right, you’ve got 马, which, if you squint, kind of looks like a horse and is pronounced “ma”. Put them together and bam! There’s “mā” the word for mother.

I’m not sure of the brain chemistry behind it, but learning the characters really helps you differentiate between Mandarin Chinese’s numerous words that are all pronounced the same. By learning the characters, you’ll have a much easier time keeping your “mā”s and your “mǎ”s straight.

Learning the characters is also essential for reading. And reading is super helpful in reinforcing and developing your grammar and vocabulary skills. There’s nothing like seeing a word from your Anki deck pop up in a book or website to really make it sink in.

So, how do you learn Chinese characters? My favorite tool by far is Skritter. If you click the link below, I’ll get a small commission. However, I would still recommend it even if I got nothing. Start with their Chinese 101 list, afterwards you can make your own lists or move on to the HSK vocabulary.

Where to Find Your Vocabulary

When you’re choosing what vocabulary words to add, resist the temptation to just add any old word you can think of. You want to focus on the most commonly used words. Supposedly, learning the 800 most common words in a language will allow you to understand 75% of it. I think 1000 words is a good target, overall.

The HSK books generally start with the most commonly used words and are a decent source of vocabulary. If you’re following the HSK levels, you’ll see that you won’t get there until about HSK 4.

Again, based on my experience and from other Chinese learners I’ve spoken with, HSK 4 seems to be about the time you reach that magical point when you can start to pick up words in context.

And yes, you will have to learn the characters of those 1000 words. That doesn’t mean you need to memorize 1000 different characters. Many Chinese words are combinations of characters, so in a weird way, the vocabulary sort of gets easier as things go on.

For example, the word 上 (shàng) means “up” or “on”. Combine it with 马 (mǎ “horse”) and you get 马上, which means “at once” or “right away”. It isn’t a stretch to imagine how you can get someplace right away when you’re on a horse.

Eventually (even before you reach your 1000 words) you can start to learn different words for things you’re interested in or you think will be useful. If you like Chinese food (and you should because it’s good) you should try and learn some food-related words, even if they might not be among the 1000 most common words.

Step Four: Immersion Therapy, Because Flash Cards Ain’t Enough

So, by now you’re be spending a chunk of time each day studying your vocabulary flashcards with Anki and/or Skritter. You’re off to a good start, but neither of these two apps, no matter how great they are, can fully teach you the language.

The whole purpose of flashcards is to prime your brain for when you see these words in a real-life situation.

I’ve had certain vocabulary words languish in my Anki deck for months. I struggle to memorize them, only to forget them a few days later. It’s incredibly frustrating.

Then, suddenly, I come across the word in real life. Maybe this is on a website, maybe on TV, maybe in a strongly worded WeChat message from my boss. Then it’s like magic. I can almost feel the word clicking into place in my brain.

I have a theory that in order to really learn a new word (or maybe even a grammar point) you need to be exposed to it in three different and separate contexts. Maybe once through Skritter, once is via your Anki deck, and one time somewhere else… bam. I have no scientific evidence to back this up, but it’s been my experience when learning Chinese.

How to Fake Immersion When Learning Chinese

Obviously, the best solution to get this exposure to the language would be to pack up and move to China. This is not going to be an option for many people. I can also say, based on experience, it still might not be enough. I am constantly amazed by how much of my life in Shanghai is lived in English.

Thankfully, the solution is pretty easy. YouTube is full of videos in Chinese. And there are a lot of videos geared specifically toward learning Mandarin. These are okay at first, but eventually, you’re going to want to watch and listen to some stuff produced for native speakers.

Peppa Pig (小猪佩奇) is an absolutely amazing resource when you first start learning Chinese. Since it’s a kid’s show it’s simple and easy to understand. They speak clearly, and you’ll also learn cool words like “恐龙” (kǒnglóng) which means dinosaur. Don’t be discouraged if you don’t understand everything at first. Feel free to use the YouTube controls to slow down the speed. Watch the episodes over again, then come back and watch them once more after you’ve studied for a few months. You’ll be impressed by your progress. You can click here for more YouTube video suggestions.

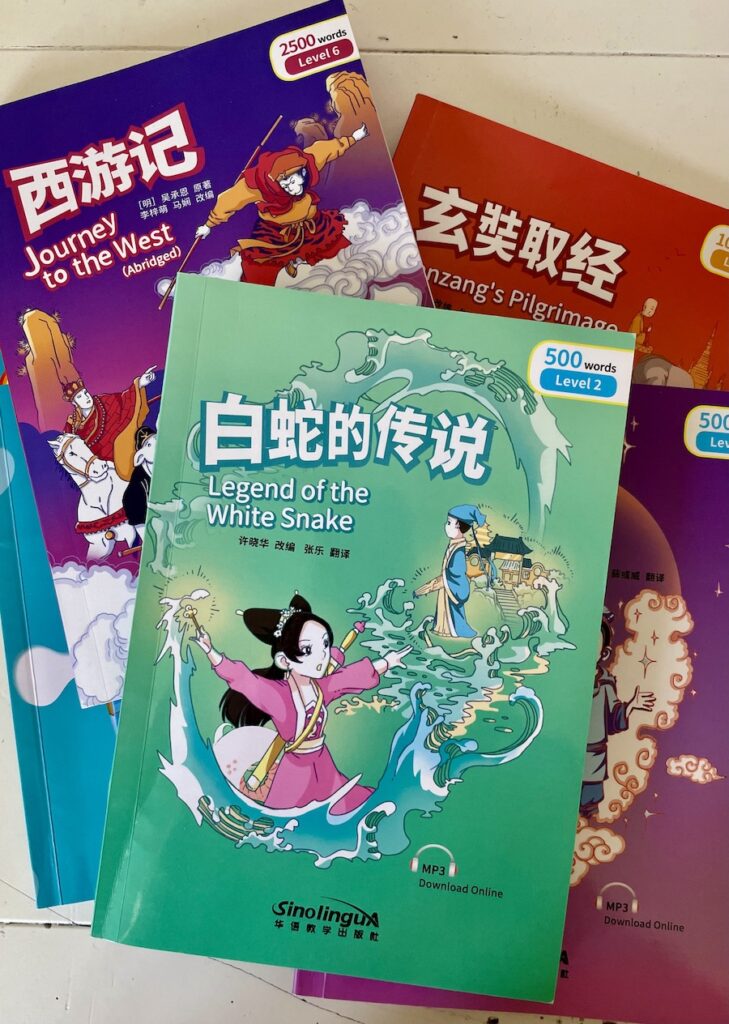

You should also practice your reading. I really enjoy the Rainbow Bridge series. The levels are logical and well-paced. The stories are all mostly classical Chinese tales and legends, so you’ll not only be practicing your reading, but you also get some insight into Chinese culture.

If you prefer staring at your phone to actual books, you can also check out Du Chinese. This app is pretty nifty; it has short articles divided up by level and you can click a word to see the English translation if you don’t know (or you forgot) what it is. There are also recordings of every article so you can practice your listening while you read. Or, if you feel like reverting to childhood, use it to listen to someone read you a bedtime story.

Finally, there are podcasts. There are a million podcasts out there for learning Chinese. Lately, I’ve been really into Tea Time Chinese, the topics are interesting and the host has a very clear, easy-to-understand speaking voice. Unfortunately, this one is a bit advanced for people just starting out. Do some searching and you’ll find something.

Step Five: The Scariest Part of Learning Chinese: Talking to People

The last step is easily the most difficult. I’ve been studying for about three years, and am around HSK 5. Theoretically, I should be able to sit and gab with Chinese people till the cows come home.

Yet, I have to be perfectly honest: I still have a lot of trouble talking to people. Take the other day, for example. I was downstairs in the middle of Shanghai’s COVID-19 shutdown, waiting in line for my daily nucleic test. One of the volunteers asked me where I’m from, and I got flustered, drew a blank, and answered “two people.”

When you finally get out of the safety of your flashcard apps, textbooks, and graded readers, you’re eventually going to have to get out in the world and communicate with some living breathing Chinese people. You are going to fuck up and make a fool of yourself. People are going to laugh at you. It’ll be embarrassing. Get used to it.

The whole reason we have language is to communicate. It’s also one of the best feelings when you can finally have a meaningful discussion with someone from another country in their native tongue.

If you’re in China, it’ll be a little easier to find someone to talk to you in Chinese, but there are a few pitfalls to watch out for. First of all, many Chinese people actually speak their own native dialect, which is often quite different than standard Mandarin. When they do speak Mandarin, they’ll often speak very fast and with a heavy accent that can be difficult for beginners.

Secondly, if the person you’re speaking with also speaks English you’re in trouble. They’ll likely switch back to English the moment you flounder or don’t understand something. People just naturally gravitate to the easiest form of communication, and if their English is better than your Chinese, guess what? You’ll end up speaking English.

How to Find People to Talk to

One option to find conversation partners when learning Chinese, then, is to find someone who doesn’t speak any or very little English. They’ll still probably speak fast and with an accent, but it’ll still be great practice. Try wandering into a random park in China and saying “你好” to some older people. You’ll likely find yourself a conversation partner who doesn’t know English and is super excited to talk to a foreigner.

If that doesn’t work, or maybe you can’t make your way to China, there are other options. I mentioned iTalki earlier, it’s not only great for lessons but also to find someone to chat with. It’s also relatively cheap, though you might have to try a few conversation partners before you find somebody to vibe with.

First, try and find someone who is able to match your level. This means speaking slow enough and clear enough. It also means someone who will stick to topics appropriate for you. I once had a conversation partner who wanted to talk about the war in Ukraine. It’s an interesting topic, but very complex and difficult enough to discuss meaningfully in English, let alone in a second language.

Secondly, make sure your partner doesn’t speak a lot of English. You should aim for 90% of your conversation to just be in Chinese, if not 100%. Again, people might want to switch to the path of least resistance and just default to English, but this isn’t going to be helpful.

You’re paying for these conversations, after all. If you wanted to discuss something with someone in English, you could just call your friends and do it for free.

Step Six: Congratulations, You Know Chinese

After a while, maybe months, maybe years, you’ll find that Chinese starts to get easier and easier. You’ll eventually be able to read things in Chinese, understand songs and movies and have actual conversations with actual Chinese people. Congratulations!

This doesn’t mean you’ll understand everything, but you’ll be able to easily figure out what you don’t know. Remember, nobody knows all the words in English either, but we can usually guess what those new words mean, or else we can ask. You’ll be able to do that in Chinese, too.

So where do you go next? Wherever you want! Through your studies, you’ll likely have come across some aspects of Chinese culture that you find especially interesting. Go out and explore those things in depth.

Just, don’t forget, you need to actually use the language in order to keep it. It won’t ever actually disappear, but you will break those neural connections you’ve worked so hard to create. Even if you aren’t going to be chatting with people in China, find some small things you can do to keep yourself engaged with the language.

Language learning isn’t something you can complete and be done with. It’s a lifelong endeavor. This might be especially true for a language like Chinese.

My Personal Routine for Studying Chinese

I have gotten into the habit of studying Chinese for at least a little bit every day. The first things I do are go through my flashcards in both Anki and Skritter for about 20 to 30 minutes depending on how many cards I want to review. I adjust this based on how much time I feel like spending or how much I want to cram.

I then typically listen to a Chinese podcast while I go for a short walk. If I’m feeling ambitious, I might try to watch some Chinese TV shows on YouTube. If I’m really motivated that day, I also might spend another 15- or 20-minutes reading. Currently, I’m working through the Rainbow Bridge version of Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Once a week (or once every couple of weeks, to be honest) I do some conversation practice on iTalki. We chat for about forty-five minutes, and afterwards I add any new words I’ve learned to my Anki deck. Every so often, I’ll also add some new flashcards based on what I’m reading or things that I’ve gleaned from text messages from neighbors or Chinese friends.

It sounds like a lot, but really it only amounts to about half an hour to an hour every day. These numbers vary based on my free time and motivation level.

Before the big shutdown, I was also taking formal classes twice a week. These are fairly intensive and each class is a little over 2 hours long. I usually skip doing all the other stuff on class days, since I figure 2 hours is long enough for one day.

I could probably study more, and maybe this is why I never became fluent in three months or whatever. However, I also work full time.

精神所致,金石为开: If You Put Your Heart Into It, You Can Break Open Metal Rocks

All these tips and steps are just my personal method for learning Chinese. You very well may find some other method or technique that works better for you. One of the most important things I’ve discovered is that language learning is a very personal thing. The key is to experiment and find a method of learning Chinese that you enjoy so that you stay motivated to keep up with it.

The last thing, and one of the other most important things I’ve discovered, is to not give up. There are times when you’re going to be embarrassed. There are going to be words that seem to constantly slip out of your brain. Don’t give up. Keep at it, and I promise one day it’ll all fall into place. 加油!